Virtual Reality

This model traces the transformations in the Rose Theatre’s architecture from its 1587 inception through several enlargements. The model is built up in VR form from the archaeological records of the foundations, using the work of theatre architects and theatre historians. This model, which includes accurate reflections of good and bad weather conditions in a London summer, makes it possible to answer questions that have puzzled theatre historians for centuries. Further, it invites users to ask new ones.

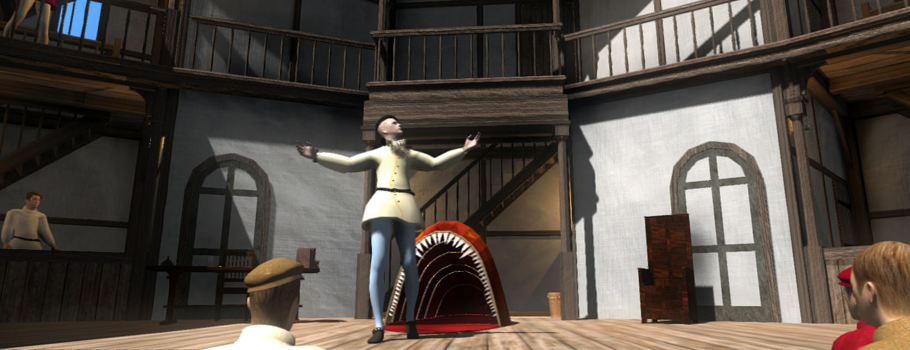

Here is a video capture of the current Rose Theatre virtual model. This model uses advanced real-time lighting and shadowing techniques. The environment is being used to explore the validity of the proposed reconstruction scenarios as well as explore the way in which this space may have been used to present theatre.

It has been revealing to explore the many props that Dr Faustus requires, as well as the many actors needed for the performance. The most remarkable prop in Dr Faustus is hell mouth, the device that appears to swallow Faustus and carry him off to hell at the end of the play. To create hell mouth as an object, we formed a large serpent- or dragon-like head with a long neck made of canvas, the open end of which was hidden in the tiring house. The head was constructed from hinged ribs that could form a jaw and provide some stability to ‘contain’ a bent-over actor who could disappear out the end, back stage. Our decisions about hell mouth’s shape and appearance were also influenced by where it would be located on stage. We abandoned trying to have it emerge from a trapdoor in the stage, unless the trap could be much larger than usual, which is unlikely on such a small stage. It would be useful for hell to be located below-stage, in terms of the vertical hierarchy of the order of beings and realms of the day, but in the play, Mephistopheles does comment that hell is all around us. Hell mouth opens and closes. In addition to hell mouth, we have also modelled the throne that descends onto the stage from the gallery above the stage (using pulleys and ropes common to ships of the era).

This video provides a sense of what the model can demonstrate. We are in the process of making the model open access so that other researchers can test their theories about the theatre and our performance of this scene. We hope to provide more examples of motion capture and scenic development in the near future.

More examples

A representation of how a man might be consumed by flames in Robert Greene and Thomas Lodge’s_A Looking Glass for London and England (~1590-92).

A representation of how the dragon might operate in a play such as Robert Greene’s ‘Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay’ (1589-90).

Motion capture scene of Dr Faustus:

Works Cited

Orgel, Stephen. The Authentic Shakespeare: And Other Problems of the Early Modern Stage. New York: Routledge, 2002. Print.

Schmidt, Gary D. The Iconography of the Mouth of Hell: Eighth-Century Britain to the Fifteenth Century. Selinsgrove, PA: Susquehanna UP, 1995. Print.